The term “laser” is an acronym that stands for “light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation”, and describes a device that emits radiation in the form of a flow of photons of light energy. Therapeutic laser has been referred to as “low level” laser and “cold” laser, but these are considered obsolete terms. They were intended to distinguish therapy lasers from surgical lasers. Surgical lasers rely on different media – gas or solid to incise or ablate tissues as an alternative to using a scalpel or cautery, respectively.

Therapeutic lasers help modulate cellular functions through a process called photobiomodulation, a photochemical process in which photons from a laser source interact with the target cells via a non-thermal mechanism to cause either

stimulation or inhibition of biochemical pathways. While the precise mechanism for photobiomodulation is not completely understood, it appears that cytochrome C, located in the mitochondria, serves as an important photoreceptor. Once light is absorbed by cytochrome C, mitochondrial respiration and ATP production increase, leading to global tissue effects.

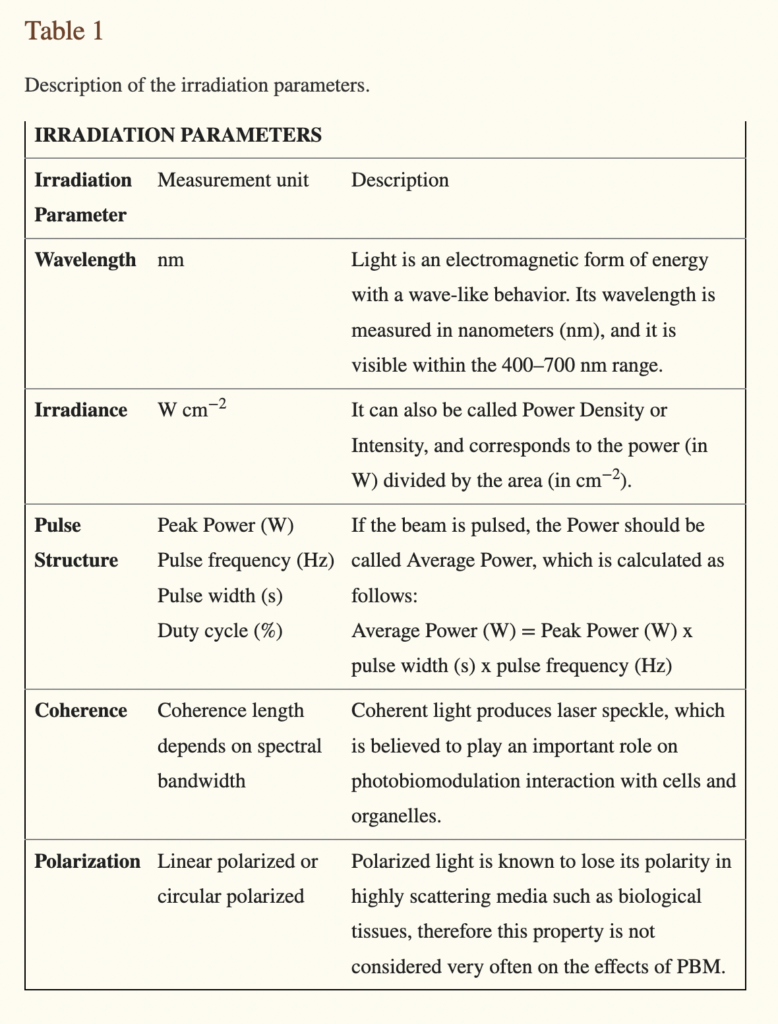

Laser light is monochromatic (one wavelength), coherent (all photons travel in the same phase and direction), and collimated (minimal divergence of the laser beam over a distance). These three properties allow the therapy laser light to be focused on a specific area of the body, to penetrate the skin without heating or damaging it, and to interact with tissue with few side effects. The beam should be aimed at 90° to the surface of the area being treated. Wavelength influences the depth of penetration, and longer wavelengths penetrate deeper into the tissues. The optimal wavelength range for tissue photobiomodulation appears to be 650nm to 1,300nm; at longer wavelengths the laser beam penetrates deeper into tissue while minimizing absorption by the pet’s hair and skin pigment. Superficial wounds and joint injuries can be treated with shorter wavelengths, while longer wavelengths are better suited to treat muscle injuries.

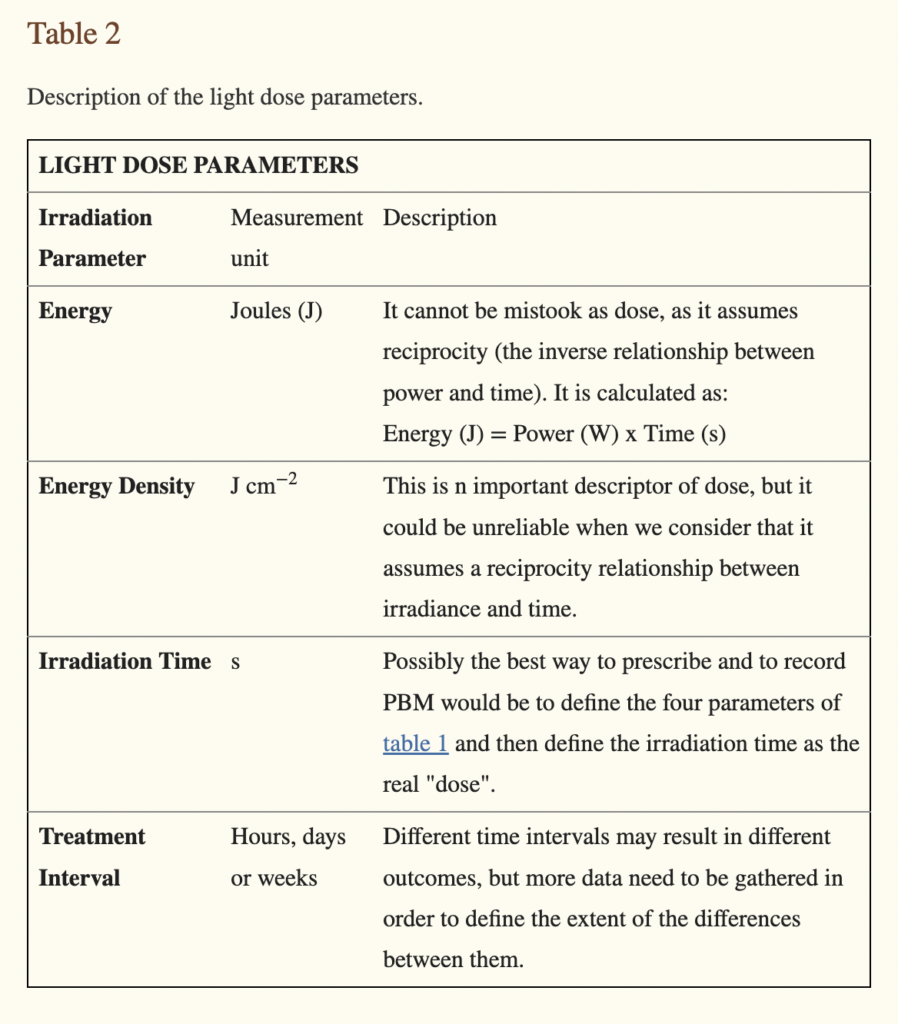

The power of the therapeutic laser matters in terms of the dose delivered, and the time needed to deliver the treatment dose. Power is a unit of time, and is expressed in watts (W) or milliwatts (mW). One watt is one Joule of energy delivered per second, and the laser dose is typically expressed as Joules/cm2 – the energy delivered over a surface area. The most commonly used therapeutic lasers in veterinary medicine are Class III lasers, which may deliver energy from 1mw to 500mw, and Class IV lasers, which deliver power at greater than 500mw.

A lower watt laser provides less energy delivery to deeper tissues so the time needed to deliver a treatment is longer. A lower power laser is better suited for treating superficial structures because of the limited power density to drive photons into the deeper tissues.

A higher watt laser allows the treatment to be delivered over a shorter period and involves administering the laser energy with a sweeping motion over the affected area. This sweeping motion may provide more complete coverage of the treatment area and may cover surrounding areas that could be causing secondary or referred pain. Pulsing of the laser beam may provide less heating of tissues at the surface while allowing for an adequate level of energy to reach the deeper target tissues, but more research is needed to define the optimal approach to a pulsed laser beam.

BENEFITS OF THERAPEUTIC LASER

Most responses of cells and tissues to therapeutic laser have been studied in in vitro models (cell culture). There appear to be many distinct benefits to using therapeutic laser for its tissue effects. Therapeutic laser has been demonstrated to relieve both chronic and acute pain by modulating peripheral nerve function and nerve conduction velocities. Laser energy increases the speed of tissue repair by increasing local microcirculation as well as stimulating the immune system and reducing inflammation. Laser energy also enhances collagen and muscle tissue development, which in turn enhances healing.

There are several important “downstream” tissue effects from the application of laser light. These effects include:

Neovascularization

Angiogenesis

Collagen synthesis which enhances wound healing

Stimulation of nerve healing

Enhanced healing of tendons, cartilage, and bones

Reduced swelling from injury

Modulation of degenerative tissue changes

Mitigation of CNS damage following traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury

When creating a treatment protocol for therapeutic laser, it is important to consider these effects in order to maximize patient outcome. The actual time the tissue is exposed to light energy may also affect the outcome.

LASER SAFETY

There are some important safety considerations when incorporating therapeutic laser into treatment protocols. Protective glasses with lenses rated to the specific wavelength of the treatment laser are important for both humans and patients in order to protect retinal tissue. Laser energy should not be applied over a pregnant uterus, over tumors, over an open fontanel, over the growth plates of immature animals, or over the thyroid gland. Be careful if the pet has a tattoo, black fur, or black skin because of the potential for light absorption and tissue heating.

WHAT DOES THE RESEARCH SHOW?

Most of the basic research done on therapeutic laser has been conducted in cell culture, and conducted in humans; however, extrapolation to veterinary medicine is reasonable.

Because of the stimulation of fibroblast activity by laser light, this may affect collagen production to facilitate healing of wounds and burns. Studies suggest a laser dose of 1 J/cm2 to 5 J/cm2. Very high doses appear to inhibit healing. Both bone and cartilage appear to respond well to therapeutic laser. Osteochondral lesions of the stifle responded well to therapeutic laser used intraoperatively. Laser may also support cartilage during times that a joint must be immobilized.

In human studies, the application of therapeutic laser for osteoarthritis is controversial. While some study participants appeared to have a positive outcome, overall results were unclear. Likewise, tendon treatment with therapeutic laser is controversial. Overall, however, laser therapy may improve collagen fiber organization, leading to enhanced tendon and ligament healing. The nervous system responds well to therapeutic laser for pain management, although the exact mechanism of suppression of central sensitization via laser is unknown.

APPLYING THERAPEUTIC LASER TO DOGS AND CATS

The optimal wavelengths, intensities, and dosages for laser therapy in pets have not yet been adequately studied or determined, but this is sure to change as studies are designed and as more case-based information is reported. To maximize laser penetration, the pet’s hair should be clipped. When treating traumatic, open wounds, the laser probe should not contact the tissue, and the dose often quoted is 2 J/cm2 to 8 J/cm2. When treating a post-operative incision, a dose of 1 J/cm2 to 3 J/ cm2 per day for the first week after surgery is described. Lick granulomas may benefit from therapeutic laser once the source of the granuloma is identified and treated. Delivering 1 J/cm2 to 3 J/cm2 several times per week until the wound is healed and the hair is re-growing is described. Treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) in dogs and cats using therapeutic laser is commonly described. The laser dose that may be most appropriate in OA is 8 J/cm2 to 10 J/cm2 applied as part of a multi-modal arthritis treatment plan. Finally, tendonitis may benefit from laser therapy due to the inflammation associated with the condition.

LASER THERAPY OF THE FUTURE

Therapeutic laser is of special interest in the area of nerve regeneration, particularly in human medicine. Veterinary patients experience peripheral nerve issues as they age, as osteoarthritis develops and progresses, in the wake of intervertebral disk disease, and when they develop nervous system decline as occurs in degenerative neuropathy/myelopathy. Photobiomodulation has been demonstrated to support nerve regeneration, re-innervation of denervated muscle, and functional recovery following peripheral nerve injury. This is an area of active research that promises to provide a significant impact on both human and veterinary patients.

SUMMARY

Therapeutic laser clearly has a role in the treatment and management of multiple conditions in companion animals. There is strong evidence to suggest that light energy at the appropriate wavelength and power density has the ability to provide modulation of tissues at the cellular level to enhance healing. There are multiple important clinical benefits that should be considered, prompting the practitioner to introduce therapeutic laser into specific patient treatment protocols. Therapeutic laser has been thought to be one of the most underutilized treatment modalities in veterinary medicine. As more and more formal studies into the uses of therapeutic laser in animal models are completed, and more and more cases are presented, there is no doubt the use of therapeutic lasers will continue to expand.

Therapeutic laser’s time has come in the treatment of many different conditions in companion animals. While it is not a panacea, it can certainly make a positive difference in the outcomes our patients experience.

The therapeutic effect always depends on the energy dose (Joules/cm2) and it is related to a number of individual physical and clinical factors, such as:wavelength, fluency, type of emission, focal distance, handpiece diameter, time, interval between sessions, number of procedures; skin phototype, site, nature, dimension, onset of the disease.